The debut of Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s new PBS docuseries, Great Migrations: A People on the Move, explores the transformative impact of Black migration on American culture and society. Interwined throughout this documentary are the roles Ford Motor Company, Michigan Central, and the city of Detroit played during the Great Migration and how it helped shape the city into a cultural and economic force that continues to evolve today.

In conjunction with the documentary debut, Ford Archives team found three employees whose relatives migrated to Detroit during this time period and showed them never-before-seen artifacts from their ancestors.

The story below is a digital interpretation of the exhibit featured at Michigan Central during a premiere event for the docuseries. Episodes air Tuesdays in February on PBS.

Great Migrations: The Detroit Story

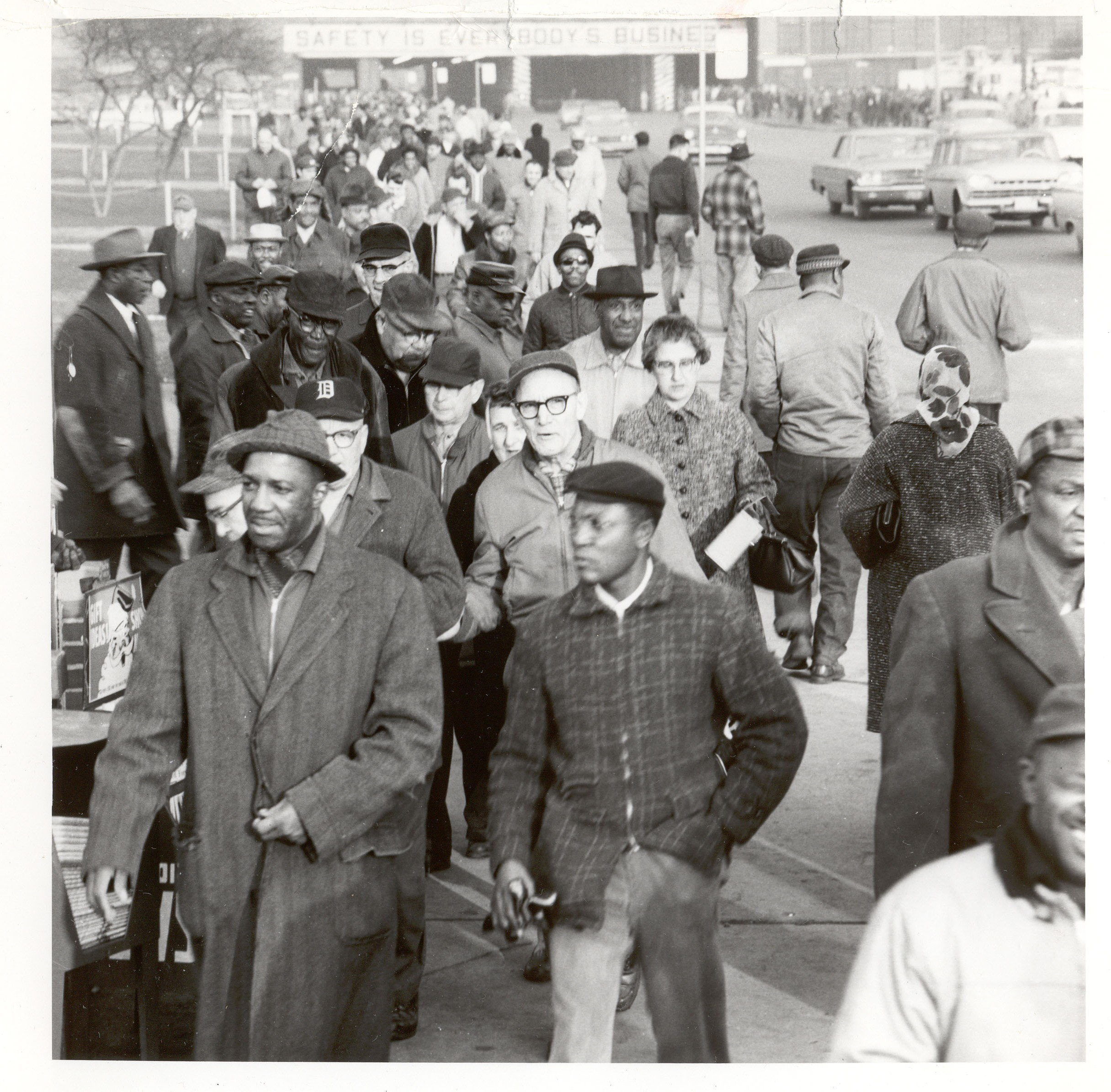

Between 1910 and 1970, six million African Americans moved out of the South and across America to build entirely new lives – a series of courageous acts that dramatically changed the fabric of American culture and society. They sought to escape the widespread discrimination and racial terror throughout the South, and the lack of agricultural work caused by the boll weevil crop failures of 1915 and 1916.

They were drawn to northern cities by the promise of expanded freedom and better job opportunities due to industrial booms and the labor shortages of WWI. And they traveled on new modes of transportation, like expanded rail service and buses, that made the epic migration possible.

Prosperity in the North was not guaranteed, and discriminatory practices persisted far beyond the South. But many African Americans got a chance in the North that was harder to come by in the South: to do decent work, earn better wages and build better lives for themselves and their families.

Detroit was a major draw in The Great Migration for a variety of reasons, including Ford Motor Company’s unprecedented high wages and trade school programs. Many Black Americans made their journey to the city through the gateway of Michigan Central Station.

Ford Offers an Unprecedented Opportunity in Detroit

Ford first offered the $5 a day wage in 1914, within months of the outbreak of World War I in Europe and the grand opening of Michigan Central Station. It was more than double the going wage, and drew 10,000 applicants to Ford’s Highland Park Plant the day it was announced. It also drew thousands of African Americans from the South to Detroit.

Ford was the first company in the auto industry to hire Black workers, and by the end of WWI in 1920, approximately 1,675 African Americans worked at Ford, making the company the industry’s largest employer of Black workers. More people moved to Detroit during the Great Migration than went to California for the 1849 gold rush.

Many new arrivals had little knowledge of assembly techniques, so Ford created apprenticeship programs and a trade school. These opportunities were part of the reason Detroit’s Black population rose 600% between 1910 and 1920. By 1970, at the end of the Great Migration, 660,000 African Americans called Detroit home – about 45% of the city population.

As Ford revolutionized industrial process, Detroit became the world’s most innovative and powerful industrial center. By 1950, one in six American jobs related to automobiles. And Detroit became a Midwestern Black mecca, where Black people could earn high wages, buy affordable property and cars, educate their children, and establish generational prosperity.

Michigan Central Serves as A Grand Gateway in the Great Migration

When it opened in 1913, Michigan Central was the tallest train station in the world and one of the grandest in the country. For many, it was the gateway to Detroit, and it quickly became the symbol of the opportunity for the city. Each day, 200 trains chugged through the station, where passengers found awe-inspiring grandeur, and public amenities including a restaurant, retail stores, waiting rooms, and restrooms that were not segregated by race. It opened just weeks before Ford’s announcement of the $5 a day wage, and quickly became a conduit for thousands of workers seeking jobs.

The station derived its name from Michigan Central Railroad, a commercial Michigan rail line that also served as part of the Underground Railroad that helped African Americans escape slavery. And during the Great Migration, Michigan Central Station became part of a journey to greater freedom.

Arriving at Michigan Central was an emotional moment for many Black Americans who journeyed from the South during the Great Migration. One traveler, 12-year-old Joseph Louis Barrow, always remembered arriving at the station from Alabama in 1926. He recalls no trace of the “colored” or “whites” signs his family had left behind.

He grew up to become Joe Louis, the heavyweight boxing champion of the world, and the pride of Detroit. And he was just one of countless travelers who brought their talents to a city that was rapidly reshaping the world.

Ford Lays the Foundation For A New Middle Class

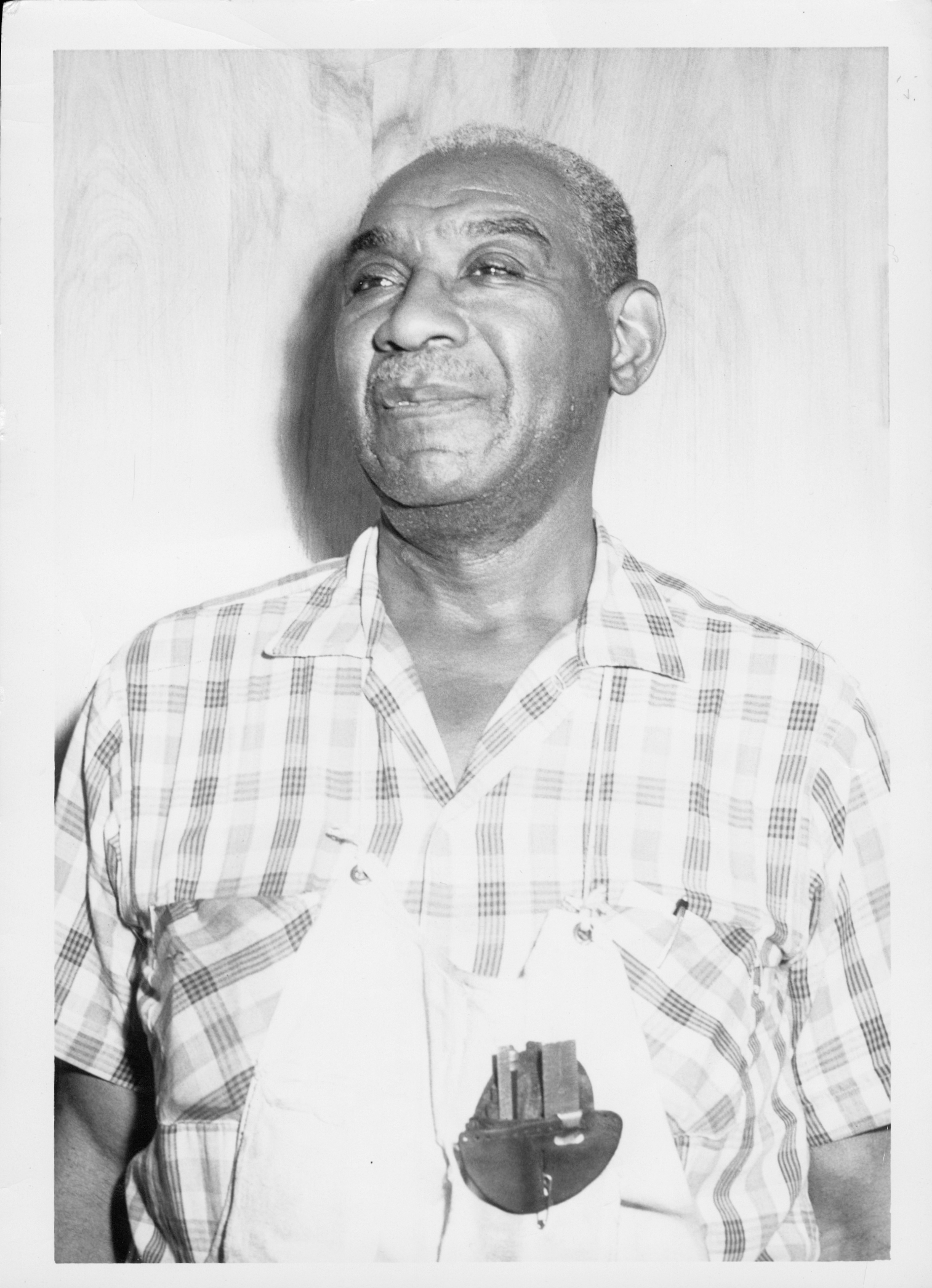

When Roosevelt Ford was a teenager in Clinton, Mississippi, the area was a hotbed of racial terror. Blight had destroyed the cotton crops, and jobs were in short supply. So Roosevelt caught a freight train to Detroit, heading for the promise of Ford’s $5 a day wage. He was hired at the Rouge in 1924, laying a new foundation for generations of middle-class life.

“Ford pays a good wage,” he told his sons. “I want all my boys to work at Ford.”

His son remembers him wearing his Ford badge with pride outside work hours, and how that badge helped him get credit at the local grocery store and respect in the community. Roosevelt Jr., his oldest son, also worked at the Rouge as an ace toolmaker. Sons Alvin and Herbert were among the first black students to enroll at the Henry Ford Trade School. And their brother Carl was the first black electrician at the engineering center.

“No question,” Carl says, “Ford has been the best manufacturing company for the black man.”

Many of Roosevelt’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren also worked for Ford, from the Rouge floor to corporate headquarters. Felicia Ford, one of Roosevelt’s grandchildren, works on the future mobility as an engineer for the electric F-150 Lightning.

“It means everything” to work at Ford, she says, where she feels like she is part of a legacy.“Ford and Detroit are going through a rebirth,” Ford said. To her, that sounds familiar: like the rebirth her family experienced when they moved to Detroit to work for Ford.

Ford’s First Two Plants Help Build Upward Mobility

Henry Ford pioneered the assembly line at Highland Park, where the $5 a day wage was first offered. Shortly after that announcement, William Perry, a Black man who had worked with Henry Ford at Ford’s lumber company, approached Henry Ford about a job. With Henry Ford’s support, Perry became the first African American hired at the company, and became a trusted advisor as the number of Ford black employees grew.

In 1917, Ford opened a second plant: the Rouge, designed to keep every aspect of production in-house, from raw material to finished product. Thousands of workers were employed on multiple assembly lines. By 1929, 8% of workers at the Rouge were African American, working as janitors, cleaners, and skilled machinists. By 1931, Ford wages supported 20% of Detroit's African American population.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Ford was the largest employer of Black workers in the city, due in part to Henry Ford’s belief that anyone who was willing and able to work should be given the opportunity to better their lives. He and leading Black ministers also formed strong personal relationships that drove Black employment at Ford plants. By 1940, almost 12% of Ford’s workers were African American, and Ford wages were a key driver of economic growth for Black Detroiters.

Detroit Becomes A Cultural Hotbed

By the 1950s, a robust black middle class had emerged in Detroit: entrepreneurs, ministers, undertakers, doctors and lawyers. They were all drawn to the kinetic city built on the foundation of the rapidly-expanding postwar automobile industry and its substantial avenues to upward mobility. Detroit was a national center of black enterprise from as early as the 1920s, with a diverse, robust roster of black businesses, along with black business associations, black insurance companies, and black financial institutions.

The relative freedom in Detroit was not complete, and when Black employees encountered limited housing options and racism, Ford supported the emergence of the Black middle class with housing, fuel allowances and low-interest, short-term loans to employees. Ford also built community centers, refurbished several schools, and ran Company commissaries that provided inexpensive retail goods and groceries.

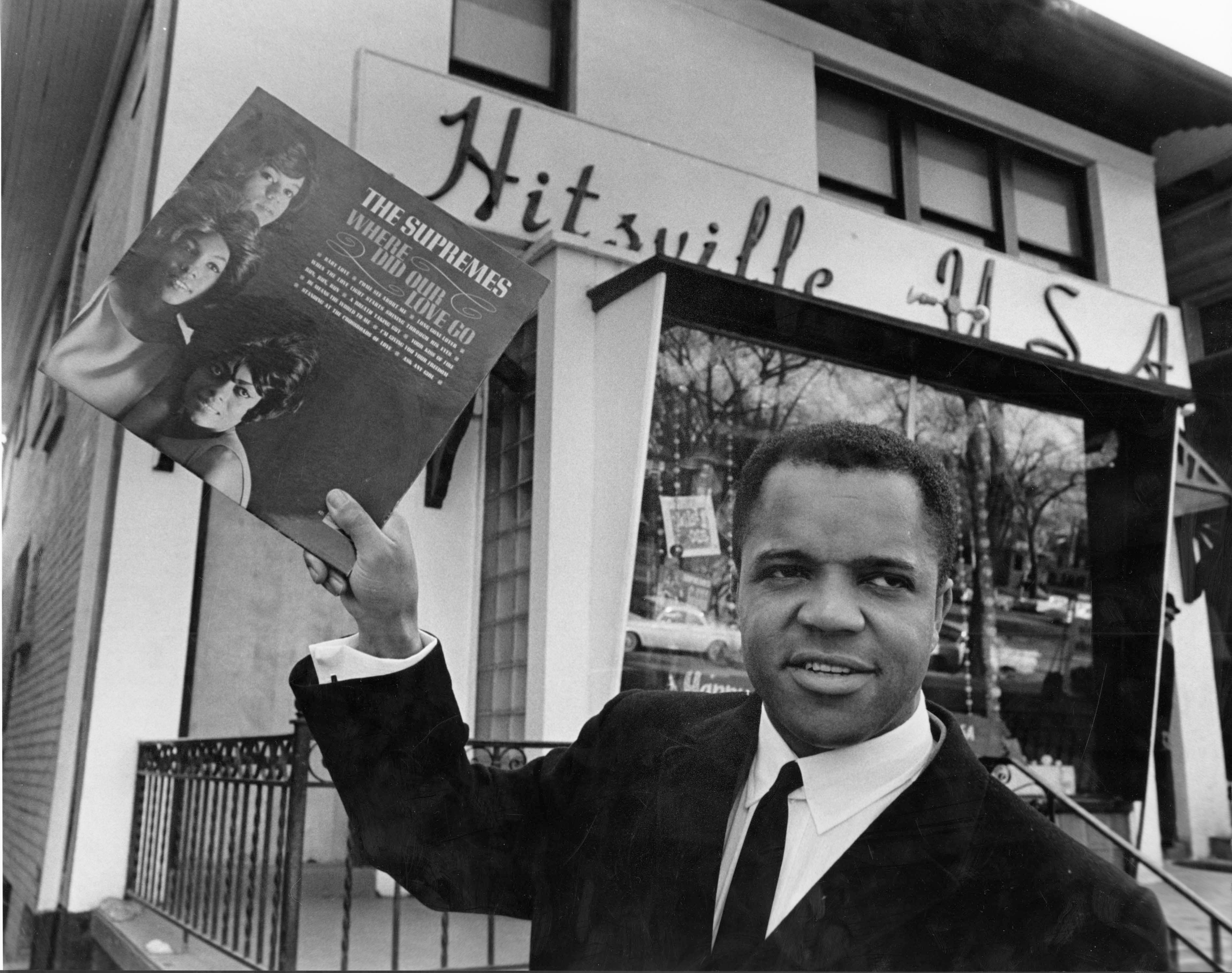

With the rise of its Black middle class, Detroit became a center of the jazz movement, as well as the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. gave an early version of his “I Have A Dream” speech in Detroit in June 1963. Berry Gordy fused Detroit industry and Black creativity to create Motown Records which he conceived of while working on the line at Ford’s Rouge factory. He saw Ford’s control of every aspect of production, and applied that model to his great love: music. His concept became one of the most powerful studios in history – and the largest black-owned business in the country.

A Family Transformed by Ford Now Works To Innovate A Better Future

Clarinda Barnett Harrison’s great grand uncle, James Moore, was the first member of her family to leave Georgia for Detroit. A veteran of World War II, he arrived in the 1940s and got a job at Ford. In the 1960s, Clarinda’s uncle Alfred Wayne Almond followed him to Detroit and found work at Ford’s Rouge plant. Both spent their entire careers at Ford and became proud retirees.

Their experiences drew other family members north, including Clarinda’s parents, who arrived in the 1980s. Today, Clarinda works building a talent pipeline for Ford at Michigan Central, with skills programs designed to attract and retain local talent.

“We’re making sure that people from Detroit have a part in the future of mobility,” she said. “We want to make sure that Detroiters can participate in that new economy, creating a resurgence of the new middle class.”

She also recruits the best mobility talent from around the globe to join in groundbreaking innovation at Michigan Central. She’s excited to see that Michigan Central has become a “magnet for talent and new companies here,” and that “the people that have been in the city, who have history here, can really be part of that vision again.” Having lived through the hard times in Detroit herself, it means a lot, she says, to see Detroit become “a real beacon of opportunity once again.”

Michigan Central and Ford: An Invitation To Innovation

After decades of service and millions of travelers, including many who were part of the Great Migration, rail travel declined at Michigan Central Station. It eventually closed in 1988 and fell into disrepair. In 2018, Ford Motor Company purchased it with a vision to restore it to its original grandeur as a hub for world-class mobility innovation. In June 2024, Michigan Central’s doors swung open again for the first time in 36 years.

Michigan Central provides innovators with the infrastructure, tools, and resources to accelerate new ideas and technologies that shape transportation, social, and economic mobility. Newlab at Michigan Central enables startups building breakthrough technologies to accelerate product development in unparalleled, real-world testing environments.

The Station is filled with workspace for innovation teams at Ford and other companies, skills development and community organizations like Google Code Next and The Boys and Girls Club of Southeast Michigan, and food, beverage and retail like The Shop at Michigan Central, Yellow Light Coffee & Donuts, and Neighbor x Folk. Ford’s Model e and Integrated Services teams moved into the Station in October 2024, and more team members from Ford and other companies will continue to move in over the coming years.

Building The Future at Michigan Central Today

Today, Michigan Central offers opportunities to build the future much like those that drew so many to Detroit during the Great Migration. Black Tech Saturdays has partnered with Michigan Central to empower Black and Brown entrepreneurs to create a thriving ecosystem in and beyond Detroit.

Google Code Next has established an immersive computer science education program to help community students become the next generation of tech innovators. Michigan Central innovation experiences like Youth Drone Demo Day inspire students from across Detroit by immersing them in the exciting world of drone technology, and the possibility that they could work in a tech field themselves.

Michigan Central also provides skills development opportunities for adults such as the ChargerHelp! EV Technician Program, teaching Detroiters how to become repair technicians for electric vehicle charging stations and certified Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment Technicians, while accommodating the schedules of working adults.

Michigan Central prioritizes engaging the communities in the surrounding neighborhoods, engaging local small businesses in discussion events for feedback and to find ways that Michigan Central can help boost these businesses success, and creating a continuous flow of community events. This included the station’s grand opening, Live From Detroit: The Concert At Michigan Central, the Summer At The Station Open House immersive museum and outdoor festivities, and Winter At The Station in November and December.

Generations Transformed by the Promise of the $5 Day Still Innovate at Ford Today

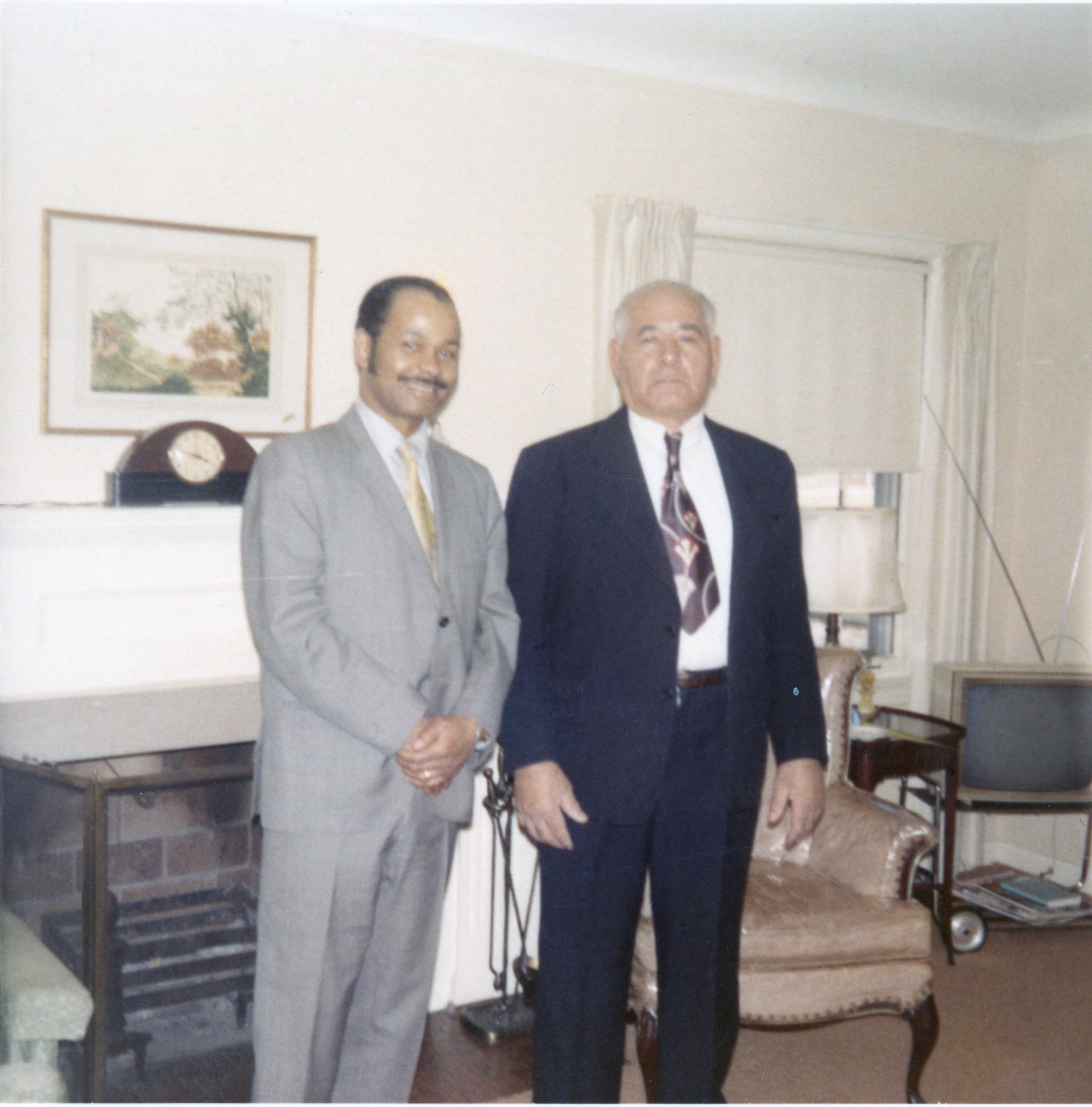

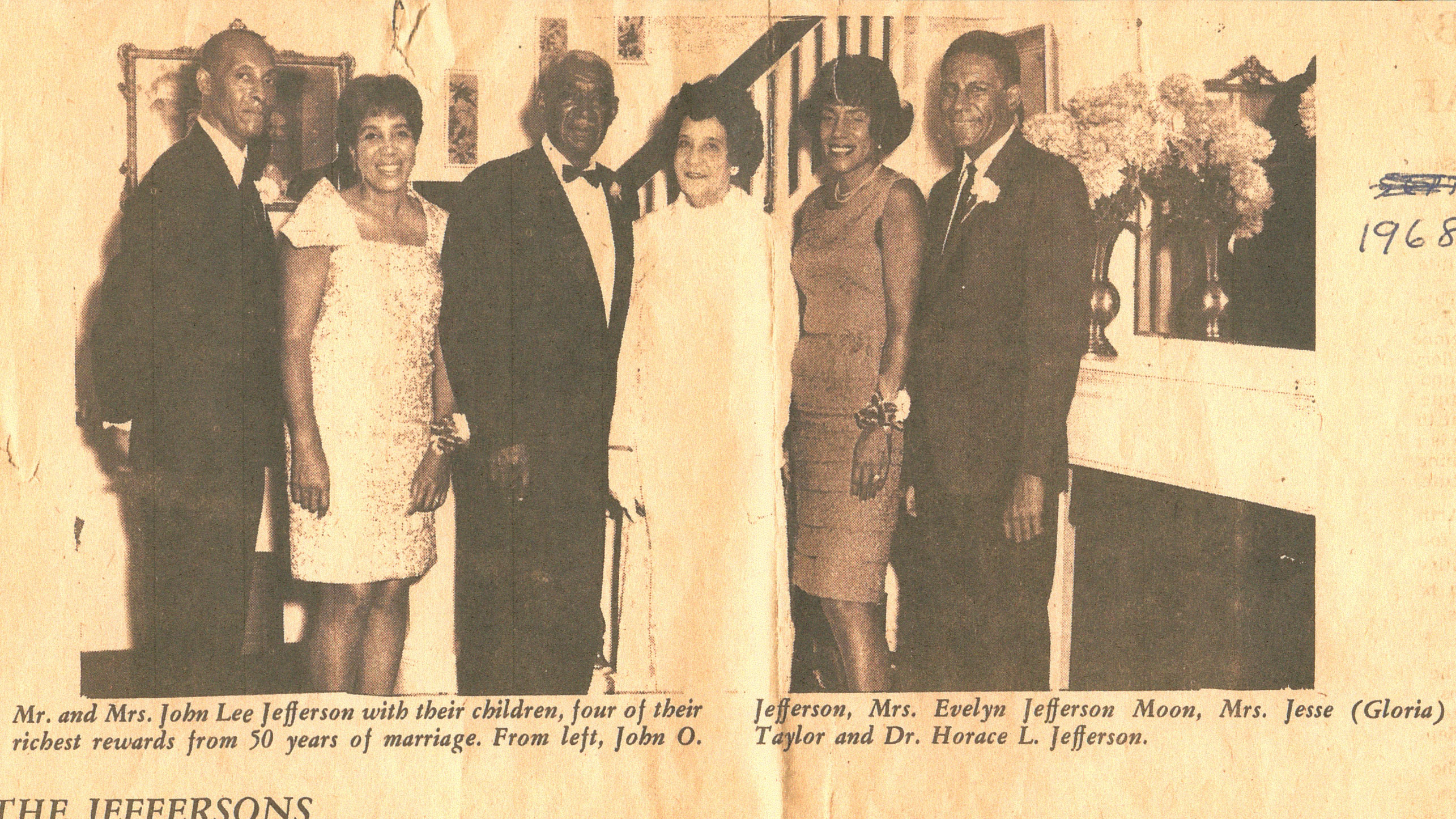

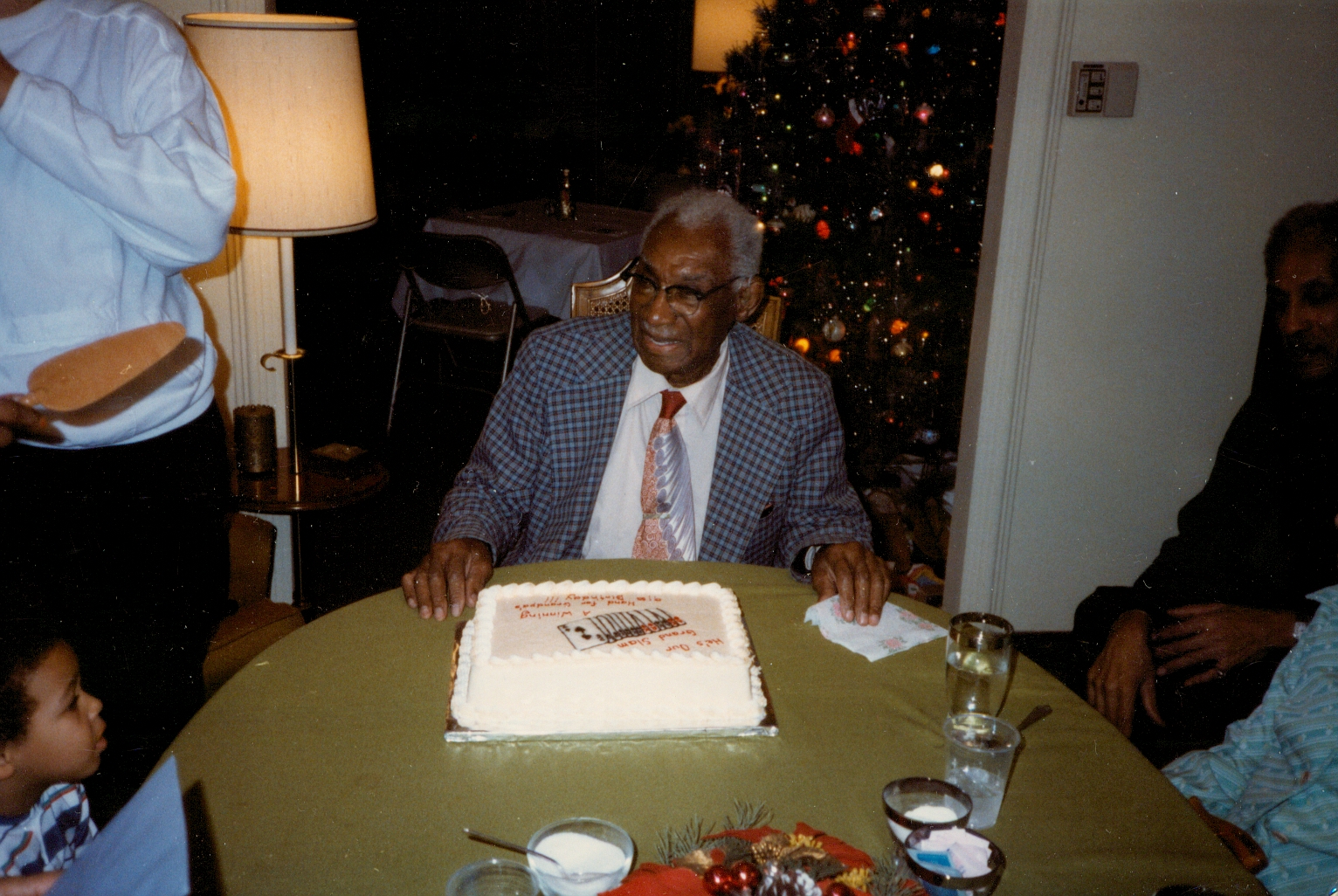

John Lee Jefferson grew up in Georgia and joined the Great Migration when he was discharged from the Army and hopped on a train for Detroit and the promise of Ford’s $5 a day wage.

“That $5 a day wage enabled people to up their level of living in those days,” his son Horace said. “That was a tremendous amount of money. It was unheard of."

When John Lee got to Detroit, he was hired at the Rouge. It took him a year to convince his wife to join him, because she didn’t like the idea of the cold. But he kept telling her, “there’s a great future here with Ford Motor Company.”

As a millwright who modified tools for different jobs, John Lee was able to weather the Great Depression and other economic shifts with his job intact.

He believed “that the Ford Motor Company gave him everything he had,” his son Horace remembered. “He was able to buy a new home, was able to raise a family.”

That initial $5 a day wage led to multiple generations becoming successful,” says John Lee’s grandson, Eric. Eric, currently a software engineer in powertrain development, has spent 24 years with the company. His son Edward has 10 years at Ford and is now a systems engineer on prototype batteries and model cars.

It’s a job he’s proud of, and one that he believes can shape not only Detroit, but the world – especially with the new innovation center at Michigan Central.

“It’s an honor to be part of it,” he says, “because you feel like you’re really making history here.”